The Monument to the Labors tells an architectural fable in outer space.

Narrated dispassionately, The Monument to the Labors imagines a future that has already been translated into history. In this recasting of the pioneer narrative, the first settlers of space are not merely brave explorers but also condemned convicts. Centering around alienation and the implications of denying humanity to the other, the story simultaneously charts the lifespan of a building: a satellite, prison, laboratory, factory, town, tomb, billboard, attraction, and symbol. These two narratives tie the privilege of dreaming to the costs of experimentation. The utopian possibilities of outer space, the great unknown, are not only the fantasies of the privileged, but also the desperate hope of the marginalized.

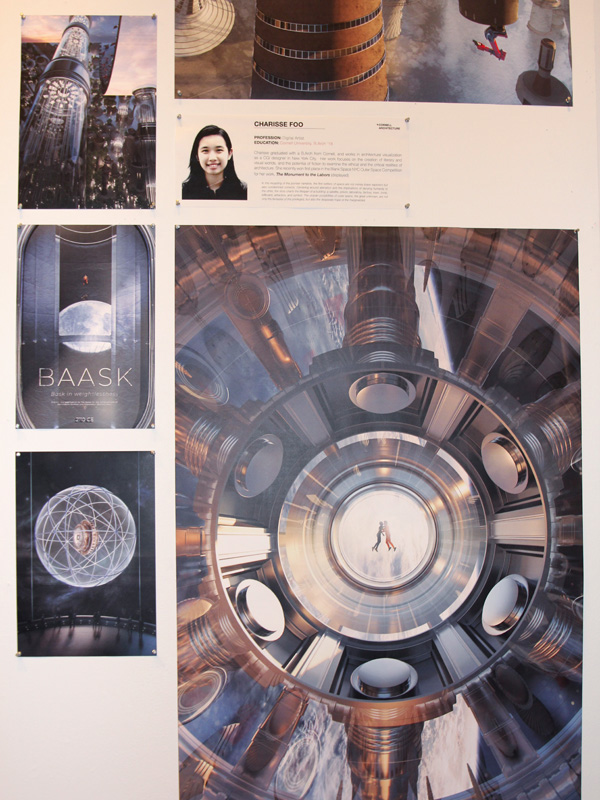

Consisting of five images and a 1,400-word story, The Monument to the Labors was awarded First Place at the Outer Space 2019 competition, organized by BlankSpaceNYC. It was subsequently featured in the exhibition ‘Architecture at the Edge of Everything Else’ at Cornell University, Fall 2019.

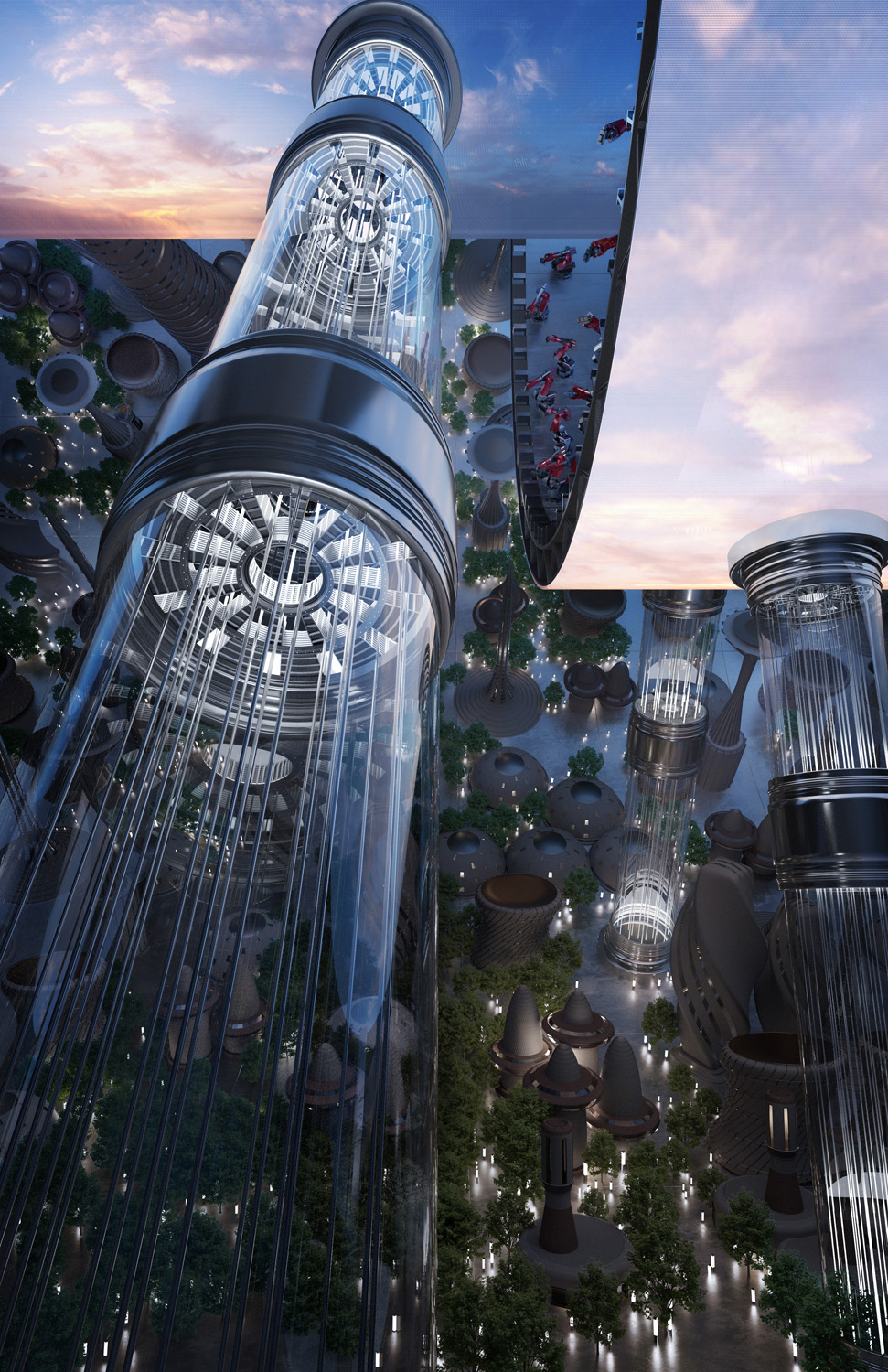

Final Images

“It is only through our imaginations that we can create change. The fanciful science fiction of the future becomes the accepted reality of today, and thus the bedrock of history upon which we stand. Congratulations to all the creative contributors, you expanded our minds!”

- Chris Hadfield, Astronaut, Juror of Outer Space 2019

The Story

They were no longer human, so what rights could they expect to have?

It was a matter of life and death. It was a matter of time. It was a matter, so to speak, of space.

Future historians would frame it differently, speaking of heroism, sacrifice, and nobility. It would take another century before the Monument to the Labors would be proposed, and another half century before it would be finally completed and unveiled, signaling a new unification in the writing of Galactic history. For what more permanent way of writing was there than building in the heavens, among the stars?

Read more

Etched in the monumental permanence of basalt-fiber-reinforced regolith concrete, outlined with titanium alloy, the Monument did not recognize the unnamed laborers, but instead magnified their Twelve Herculean Labors. A young doctoral student, in a moment of low-g headiness, had seen in the almost-forgotten Greek hero something that was neither god nor human: an alien, reaching towards immortality. Proof of heroism and penance for wrongdoing were two sides of the same coin. It was unlikely that the Committee for the Construction of Galactic Infrastructure appreciated all this; they had simply approved the project’s high Predicted Cultural Value rating for a low Total Construction Cost. The numbers spoke for themselves.

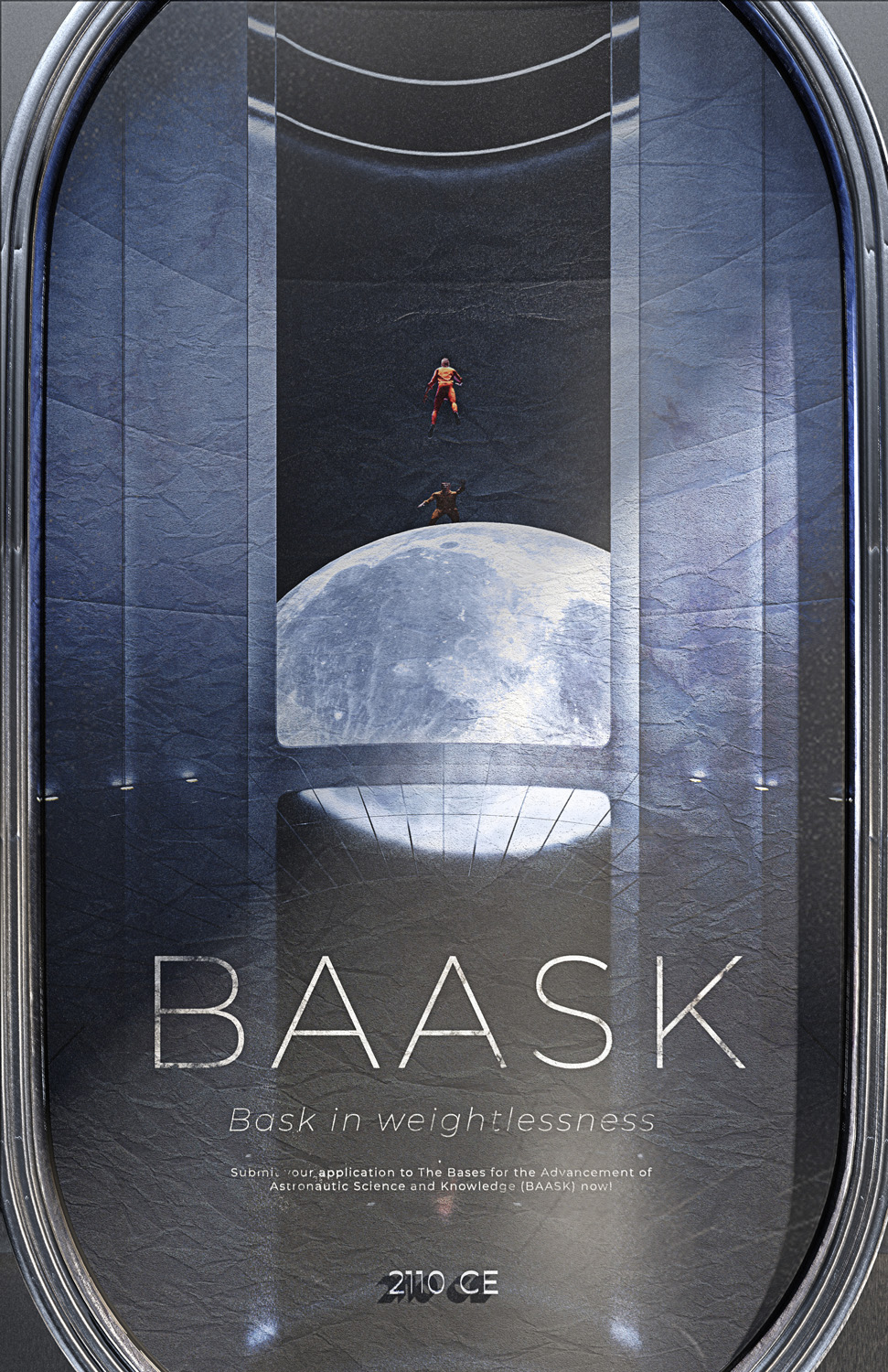

It had been the numbers that had led to the creation of The Labors, then called Bases 1-12 for the Advancement of Astronautic Science and Knowledge (BAASK). After the 2100 Century Launch Disaster, outer space had lost its glamor. SpaceTrak and SpaceTransit were now in deep recession, and the towering empty bulk of the space elevator terminals spelled the end of their golden age. Humanity retreated, and the undiscovered country of outer space fell to those who had nothing but their lives to lose: the convicts.

The concept was simple: a reduced sentence for service to humanity. Ghost cities existed in space, robotically built, half-complete. The space bubble had burst, and the Laborers were tasked with piecing the remnants together to save their own lives: they were to build their own space in the universe. BAASK needed construction, mining, terraforming, maintenance, farming, manufacturing – the hard labor of colonization, reliant on half-tested life-support systems. Yet the BAASK campaign emphasized the gathering of experimental data based on humans living in space. Bask in weightlessness. Bask in the light of the stars. Bask in endlessly open space. In the closed prison environments where BAASK advertisements were concentrated, they had an explosive effect. The population of the incarcerated had grown steadily; living conditions inside were at an all-time low. To all involved, BAASK was a way out. Escape. Each inmate served half their time in space, for a minimum of five years; after the completion of their sentences, they would be offered the status of Galactic citizens. A place among the stars. Applications poured in and were just as rapidly approved; within weeks, tens of thousands were shipped into space. Upon leaving the Earth, however, all Laborers lost their Earth citizenship, rights, and privileges: for all intents and purposes, until the successful completion of their BAASK term, they were aliens.

Owing to tight media control over the BAASK project, the Laborers were silent. No statements were ever issued, or interviews granted. An estimated one million Laborers left Earth for the Bases from 2110 to 2145. No one returned.

The Monument was, in fact, an abandoned space city that had originated as Base Seven. The oldest surviving Base, Base Seven was the property of ex-convict space tycoon Madelyn Rose, a legendary Laborer who first entered it as a prisoner in 2112. A short cylinder with a central weightless column, Base Seven was a satellite city in low earth orbit, designed to achieve 1g pseudo-gravity for long-term settlement. Designed to house 10,000, it had supported a population of 30,000 in its last days. Legend had it that Rose herself was buried in the center, making the entire structure the largest tomb known to mankind. The rumor had been systematically disproved by the authorities, but it persisted, and undoubtedly contributed to the high Predicted Cultural Value rating the Monument received, enabling its rapid approval.

Critics alternately lauded and lampooned the Monument for being an unabashed successor to passé-21st-century-glass-box-architecture. Put a glass box around it. Float the glass box. The building is a lantern! The Monument was all these things, and the controversy added to its high Predicted Cultural Value rating. It was a glass sphere encasing the ruins of a city, orbiting the Earth. Powered by a nuclear fusion core, it was a star in the night sky. It was an impossibly large feat of engineering and material science, clad with metallic glass with unheard-of structural strength and held together by graphene composite fibers. A marvel of art and science. A monument to the past, a prototype for the future. Construction was sponsored by the two leading space manufacturing companies, one of which was owned by Rose’s estate. It was the largest billboard in the world.

When Madelyn Rose arrived in 2112, Base Seven had been pristine, virgin territory, half constructed by machines that now stood silent, waiting. Upon remote activation from Earth, the Base started spinning, but – who knew if it was a mistake or malice – at a pseudo-gravity of 5g instead of 1g. The Laborers were thrown into a panic as their bodies strained to obey them. Bodies fell; bones broke at whim. Fear, anger, and despair raged. Within a week, half the Laborers were dead. The data was sent to Earth. In the chaos, Rose had been one of five Laborers who had made the excruciating journey up to the central axis of the base, a weightless column, where they had jammed the engines so that the Base stopped spinning. Below them, bodies that had been bent double now swam in the air like babies, wide-eyed, frightened and excited. As backup power kicked in, robotic construction crews whirred into life, deploying themselves to 3D-printing habitats in the first suitable site encountered. The Laborers clumsily hauled supplies in their new weightless world, watching in awe as a robotically-constructed jungle grew up around them. Foundations were anchored to all surfaces and houses sprouted, layer by layer, from them. A new universe was born.

Rose herself rose in power and prestige, falling in love – or was it an alliance? – with Terry Samuels, the leader of neighboring Base Two. On her first day of free Galactic citizenship, she married Samuels and bought over the sky – the perfectly reflective central column of Base Seven, where she had once sabotaged the engines. It was the only private space in the panopticon Base, with one-way mirrored walls that showed the entire city surrounding her. She had built her empire, and here it revolved around her.

For half a century, under Rose’s ownership, Base Seven became the center of the thriving space manufacturing industry, overtaking the market for fiber optic cables, and pioneering the construction of liquid metal, a metallic glass alloy that quickly became a staple for space construction. As BAASK faded into history, Base Seven came to house 30,000 factory workers, doubling in on itself with the construction of mezzanines, nested cylinders inside the main volume. Workers would refer to The Day the Sky Fell, when a new sky would appear above their heads, much nearer than before. The skies themselves were LED screens displaying images of Earth’s skies, one of many worker welfare measures. The Base eventually consisted of five nested cylinders, the outermost ring rotating at 1g. Weightlessness would not suit the newcomers from Earth. After a near-fatal fall in the 1g ring, Rose herself never left the innermost weightless column, saying her body had become alien. A crushing defeat, or crowning victory? No one dared ask.

Five years later, Rose moved operations to one of many newly-constructed satellites. Base Seven, in its malfunctioning obsolescence, was methodically stripped, sealed, and left empty to orbit the Earth: the cheapest solution. It was this shell that formed the core of the Monument to the Labors.

Tourists would not know all this. They whispered that the Monument was engraved with a secret code that Rose created. They whispered that her body still floated in the center of the Base, lit eternally by the newly-installed fusion core. They gazed at the Monument in awe, and shuddered before they could explain why.

Exhibition

It was an honor to have The Monument to the Labors featured in the exhibition Architecture at the Edge of Everything Else at Cornell University, Fall 2019. Curated by the Department of Architecture, the exhibition draws from Esther Choi and Marrikka Trotter's book, Architecture at the Edge of Everything Else, and highlights "individuals who have done significant work outside the traditionally held limits of the profession."

From the exhibition text:

We can no longer sustain the separation of architecture as a profession from all other creative activity. We are faced with so many extraordinarily urgent and necessary issues today that need new minds and new approaches. Because architecture, as a practice, is inherently collaborative, multifaceted, and dispersed, it is ideally situated to explore deploying architectural ideas or techniques outside of what is traditionally considered "the profession."

Many, many thanks to Evan McDowell and Sam Kim for the exhibition photographs.

Process

The Monument to the Labors was the first CGI personal project I'd done, and will always have a special place in my heart. These early thumbnail sketches were the genesis of the final images, which were created with 3DS Max, Corona Renderer, and Adobe Photoshop. The short animations below give a glimpse into the post-processing that happens in Photoshop. I am forever grateful to my wonderful colleagues at DBOX, who taught me so much about CGI, architectural visualization, and storytelling.

Important influences were Liu Cixin's Three Body Problem (Remembrance of Earth's Past) trilogy, as well as MIT's Beyond the Cradle (2019) conference. NASA's Kaplana One satellite design and its skilful visualizations by Bryan Versteeg were invaluable resources. Finally, the character of Rose is a nod to Rosetta Pracey, wife of Samuel Terry (1776-1838), an ex-convict who became the richest man in Australia's history.